Meeting the Park Needs of All Californians

2015 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan

California's 150-year park legacy created one of the world's greatest systems, with nearly 1,000 agencies managing 14,000 parks. This plan provides pathways to continue the legacy throughout California.

Forward

The California Department of Parks and Recreation has entered an exciting and challenging two-year, focused, effort to transform the State Park System. The February 2015 Parks Forward Commission report identified a Parks Department that is in need of major operational improvements and recommended "A New Vision for California State Parks". We have taken their advice seriously and prior to their final report, launched a two year Parks Transformation process that will fundamentally change how the Department's services are provided in future years. The Transformation Team has developed an Action Plan that will enable the Department to become more relevant to California's emerging diverse and underserved communities, to increase partnerships of all kinds, to use the most advanced technology and management tools, and to develop excellent management systems that will sustain and enhance our services for future generations. Additional information about the Transformation Team effort can be found by visiting www.parks.ca.gov/TransformationTeam.

The Parks Forward Commission report highlights that oftentimes local park agencies are best at providing services to local communities, especially traditionally underserved communities. California's 2015 SCORP complements the Parks Forward Commission report and the efforts of the Transformation Team regarding increasing park access to all Californians. This SCORP recognizes the important role that approximately 900 local agencies have in creating and maintaining close-to-home parks within communities throughout California.

Together, we have an opportunity to achieve excellence as we transform California's treasured park system into a world class model; I invite you to join me in this pursuit.

Lisa Ann L. Mangat, Director

California Department of Parks and Recreation

State Liaison Officer for the Land and Water Conservation Fund

Executive Summary

California State Parks' 2015 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) reflects the current and projected changes in California's population, trends and economy.

A SCORP is required of every state in order to be eligible for grants from the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act. Over the past fifty years, LWCF grants have created or improved over one thousand parks throughout California. California's 150-year park legacy created one of the world's greatest systems, with nearly 1,000 agencies managing 14,000 parks. This plan provides pathways to continue the legacy throughout California.

This edition of the SCORP provides a strategy for statewide outdoor recreation leadership and action to meet the state's identified outdoor recreation needs. This SCORP is a product of the California Department of Parks and Recreation ("State Parks") that holds the authority to represent and act for the State in dealing with the Department of the Interior for purposes of the LWCF Act of 1965, as amended. The action plan is derived from public input and a statewide evaluation of existing park and recreation lands.

Public participation for this SCORP's development included:

- Focus Groups: 81 health and recreation experts through six focus groups throughout the state.

- Director Survey: 295 public agency director respondents.

- Public Survey: 5,421 adults and 410 youth respondents through the Survey on Public Opinions and Attitudes (SPOA).

California Develops New Tools to Assess Park Need

The California State Park's new Geographic Information Systems (GIS) tools represent the nation's first interactive statewide analysis of park availability and demographic information at the neighborhood level. This increased information will allow for an analysis of park access to enhance park planning efforts for Californians. These tools are available at www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP.

Section 6(f)(3) of the LWCF Act requires that property acquired or developed with LWCF assistance shall be operated and maintained for public outdoor recreation in perpetuity. In many cases, even a relatively small LWCF grant in a park of hundreds or thousands of acres provides Section 6(f)(3) protection to the entire park site. Changes to a 6(f)(3) protected park to a use that is inconsistent with public outdoor recreation requires the National Park Service's approval.

Products of California's 2015 SCORP

- Meeting the Park Needs of All Californians: 2015 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan

- Survey on Public Opinions and Attitudes on Outdoor Recreation in California (SPOA) document, and on-line SPOA tool

- Outdoor Recreation in California's Regions

- Economic Study on Outdoor Recreation in California

- Alternative Camping Survey

- California Recreational Trails System: Collaborative Lessons from the Pacific Crest Trail, California Coastal Trail, and Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail Reports and Maps

- "Parks for All Californians" website at www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP which includes links to products 1–6 and:

- Park Access Tool (GIS)

- Community Fact Finder Tool (GIS)

- Grant Allocations Tool (GIS)

- Explanation of GIS tool data methods

- Success Stories clearinghouse

- Partners listing and links to their web sites

- Action page with annual updates

California's last SCORP was updated in 2008. This 2015 SCORP improves upon the 2008 SCORP. The seven products listed above were developed with LWCF planning grants as part of California's 2015 SCORP. This document summarizes key findings, introduces new GIS tools to assess local park needs, and establishes priorities for statewide actions including the use of LWCF allocations to California. For further guidance on how to submit LWCF funding applications, including Project Selection Criteria, go to www.parks.ca.gov/grants_lwcf .

I. California's 150-Year Parks Legacy

Yosemite Park in California set the stage for the legacy we enjoy today. In 1864, President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant Act, ensuring the land would be held for public use and recreation and would be inalienable for all time. The 150 years that followed brought commitments for stewardship of open space and parks for nearly half of the state's 100 million land acres.

Birth of State and National Parks in California

During the "Gilded Age" of the late 1800s, the effects of rapid urbanization began to adversely affect the natural environment. Old growth forests and spectacular landscapes were being destroyed. Responding to this trend, the Sempervirens Club, Sierra Club, and Save the Redwoods League promoted parks as a means of protecting California's natural resources for future generations.

Early City Parks in California

During this same era, cities began developing parks to provide urban residents with close-to-home connections to nature. News outlets in the late 1800s called parks "the lungs of the city."

Three examples of the nation's most visited and largest city parks created in the 1800s include:

- Balboa Park, San Diego (1868)

- Golden Gate Park, San Francisco (1870 State bonds built park; 1887 built nation's first public playground)

- Griffith Park, Los Angeles (1896 Griffith J. Griffith donation of 3,015 acres to Los Angeles for recreation)

Building for the Future

The state's public lands legacy expansion became a reality through the statewide bond acts, regional and local taxes, federal support and political planning, and regulatory decisions. Through these opportunities, every Californian has helped build this system by devoting taxes and support, often through volunteer assistance.

Understanding Park and Open Space Data

California has a land mass of 100 million acres. The analysis in this SCORP (Section III, page 15) relies strongly on the California Protected Areas Database (CPAD). CPAD is a GIS inventory of all lands owned outright for park and open space purposes by public agencies and certain non-governmental organizations. Learn more about CPAD at: www.CALands.org .

Defining Recreation Lands in the SCORP

While California has a land mass of 100 million acres, this SCORP focuses on the 47 million acres statewide that remain open and could be used for recreation. These areas include:

- City and neighborhood parks

- Outdoor recreation areas, such as greenway trail corridors and public beaches

- Regional open space preserves and parks

- State and national wildlife areas

- Recreational lakes and reservoirs

- State and National parks and historic sites

- National forests and other associated public land

Lands Not in SCORP Analysis

Not included in the SCORP's focus on 47 million acres are other non-recreational open space lands in CPAD because they have restricted or no public recreation access. Examples are below:

- Areas of public land that do not have a formal recreation use (such as a trail) and are not adjacent to public recreation areas (such as some Bureau of Land Management parcels)

- State and federal wildlife refuges that are closed or have restricted permits for public access

- Other areas, including some watershed and related lands that are closed or have restricted permits for public access

In addition, some types of recreation locations are not included in CPAD at all, and therefore not included in the SCORP analysis:

- Schools are not counted in CPAD

- Sites that only provide indoor recreation (such as a community center that is not within a park) are not counted in CPAD

- Private recreation lands, such as golf courses, privately owned hunting areas and commercial campgrounds

- Conservation easements held by public agencies or land trusts that usually are operating farms or ranches. These easements are tracked in the California Conservation Easement Database (learn more at www.CALands.org/cced)

Who Owns Recreation Lands?

By number, parks are mostly owned by city, special district and county agencies

[chart] City 9,000 County 1,200 Special District 1,700 State 631 Federal 500 Non Profit, other 450

[chart] By acres, parks and open space are mainly owned by federal and state agencies City 316,000 County 238,000 Special District 445,000 State 1,990,000 Federal 43,700,000 Non Profit, other 210,000

Park Partners Responding to Park Needs

California's 150-year parks legacy has been created through the actions of nearly 1,000 public agencies and nonprofits. These park partners reflect the diversity of the state's park needs:

- Local agencies — provide close-to-home heavily built-out active recreation facilities, such as sports courts/fields and community centers (plus some broader open space roles) — includes city, county, special district/recreation districts.

- Regional agencies — conserve larger landscapes/habitats and provide hiking, camping, etc. in large open spaces — includes regional park and open space districts and joint powers agencies.

- State agencies — preserve significant natural and cultural areas. Facility development in State Parks, by law, must complement parks' natural/cultural integrity. The Department of Fish & Wildlife, 10 state conservancies, CALFIRE's forest areas, lands of the Department of Water Resources, the State Lands Commission, and state university preserves all protect fish and wildlife resources, forests, and broad areas of public land.

- Federal agencies — primarily conserve iconic natural and cultural resources and sites, rather than providing developed recreation. This is accomplished through the National Parks System, the refuges of the Fish and Wildlife Service, the vast National Forests, deserts and other public lands overseen by the Bureau of Land Management and lakes and reservoirs from the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation.

- Non profits / Other — land trusts and community organizations often own publicly accessible preserves and neighborhood parks or partner with public agencies to offer programs and services. The health sector, foundations, and businesses contribute funding and the people of California volunteer time and resources to support parks.

The California Department of Parks and Recreation

California has benefited greatly from this system of both public and private agencies that have made parks a priority. The California Department of Parks and Recreation serves an important role in this system. The Department's roles include the following:

- State Park System — Protect landscapes where nature is primary and facilities complement natural and cultural/historic values: 279 State Parks care for 1.59 million acres for future generations, including almost one-third of California's scenic coastline.

- Develop and maintain the SCORP — Develop analysis, goals, tracking systems and range of partnerships to achieve plan, including facilitating discussion and outreach about plan goals and programs.

- Fund Local Needs — Develop and administer local assistance grant programs from bond acts or federally or state funded annual programs through the Office of Grants and Local Services and the Divisions of Boating and Waterways, Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation, and Office of Historic Preservation. Since 2000, the Department administered over $2 billion in grants.

- Facilitate planning, technical assistance, and funding partnerships — between the health sector, local park agencies, and other sectors to build healthier communities through new parks and programs.

II. Why Parks and Recreation Matter

Parks and recreation matter in many ways to California's 38 million residents. Every day, millions walk, ride, or run through parks, play with friends, and absorb the wonder of nature.

Families and organizations have many needs; among them are the needs for recreation and access to the outdoors. Parks and recreation:

- Support healthy, affordable, physical and social activities

- Improve the quality of life in communities as a form of social equity and environmental justice

- Provide venues for cultural celebrations that can anchor communities

- Are economic engines that fuel tourism, provide jobs, and enhance the value of neighborhoods

- Preserve historic sites that connect Californians to the past and safeguard its future

- Protect California's inspiring vistas, natural resources, habitats, watersheds, forests, and wetlands.

In addition to these direct benefits, the process of planning, creating, using, and improving parks can generate positive change. Community based planning gives stronger ties to one another and safeguards our neighborhoods, bringing people and the governments that serve them closer together.

"It is so surreal to stand here knowing this will become a soccer park. It will build kindness in our community. Here, youth will learn pride-with-purpose and become fit. We have seen kids turn their lives around through sports."

Physical, Mental and Social Health

Public parks and recreation opportunities serve as gateways to a healthier America.

Recognition of many health challenges demands various responses. Parks can help with many if not most of these challenges: obesity; life expectancy; immune systems; general risk of disease; and overall quality of life.

Parks as social meeting places also grow community health — encouraging more volunteering, social engagement, and civic pride. Parks provide affordable places to exercise. Youth join teams and enrichment programs in parks. Parks serve as strong catalysts in reclaiming urban run-down areas, and even contribute to environmental health — park vegetation can clean some pollutants improving local air quality.

Examples of health benefits include:

- Adults and youth who live close to parks experience higher physical activity levels. An international study by the University of Exeter's Medical School (Environ. Sci. Technol., 2014, 48 (2). pp 1247–1255) also found that parks nearby provide psychological benefits — as much as a one-third decrease in mental health issues (anxiety, depression).

- Adolescents with easy access to multiple recreation facilities experience more physical activity and are less likely to become overweight or obese than adolescents without access to such facilities.

- In distressed neighborhoods where vacant lots were converted into small parks and community green spaces, residents reported significantly less stress and more exercise, according to a 2011 study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

- Through a youth community gardening program implemented by 20 park and recreation agencies, 51 percent of participants reported eating more fruits and vegetables. Parks can provide fresh food through community gardens, horticultural, and fruit tree orchards.

The health benefits of parks aren't just a matter of feeling positive about park-based recreation: a 2011 study conducted on a city park and recreation system revealed that the city's residents were able to save $64 million in annual medical costs as a result of getting physical activity in city parks. For individuals, the annual medical cost difference between being active or not was as much as $250–500.

"I made it a goal to walk two miles each day on this park's track with a group of retired friends. Then I use the outdoor gym equipment. I lost many pounds. It is a positive movement to a healthy lifestyle."

The Importance of Play Areas for Children

Play is vital for the health in children. Health professionals agree that the decline of active outdoor play in childhood is linked to the rise of childhood obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and decreased life expectancy. The American Academy of Pediatrics, in its 2007 clinical report titled "The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds," urged doctors to advocate for active free play as an essential part of every child's physical health.

A 2004 study by Frances Kuo and Andrea Taylor, published in the American Journal of Public Health, found that play and other activities conducted in green outdoor settings significantly reduced the symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children. The number of children diagnosed with attention problems has skyrocketed in recent years.

Free play is the engine of learning in childhood — a vital force in children's cognitive, social, and emotional development. Providing rich and stimulating outdoor environments for children to play is important.

California Develops New Tools to Assess Park Need

The Children's Outdoor Bill of Rights was developed by the California Roundtable on Recreation, Parks and Tourism and has this objective: Every child in California, by the completion of their 14th year, should have the opportunity to experience each of these activities:

- Play in a safe place

- Explore nature

- Learn to swim

- Go fishing

- Follow a trail

- Camp under the stars

- Ride a bike

- Go boating

- Connect with the past

- Plant a seed

More information at http://calroundtable.org/Copy_of_cobor.htm .

Removal of Blight to Create a Park — "Our community is polluted and unhealthy. We have been trying to get people to hear us that we need a park with trees, grass, lighting, a place to socialize, exercise and play. Turning this site into a park will improve our community image.

Environmental Justice

While the concept of environmental justice grew out of the disproportionate placement of harmful facilities (dumps, refineries, toxic sites) near people of color and of below average incomes, it applies here, too: the absence of positive things, like parks, can also be harmful. Communities need nearby parks to enjoy many of the benefits described in this section.

Research findings (Godbey and Mowen: The Benefits of Physical Activity: The Scientific Evidence) also show that children who live close to public parks and recreation facilities are more likely to be active. Given the huge challenge of obesity facing so many children, particularly children of color, anything that increases active living is a matter of justice, as well as of health. Public parks also provide a pathway to enrichment programs that are more easily available to more well-off communities, such as special camps, gyms, and private sports activities.

Critical to addressing environmental justice is the development of a positive sense of community. Parks can beautify areas of blight. Parks serve as grand meeting places of diverse populations. Engaging with all of our diversity on a regular basis is something that nearby parks can easily offer — and all of society benefits as the bonds of citizenship grow through these interactions.

Celebration of Cultural Heritage

California, as one of the nation's most diverse states, contains parks that are actively used to celebrate cultural heritages. Memorials about the park sites themselves, with stories placed into interpretive facilities, public art, and interpretive programs, show the depth of California's diverse heritage.

The festivals and celebrations of all types that take place in parks represent important cultural assets. From birthday parties and weddings, to national and international holidays, to festivals and special performances, parks embody California's collective culture.

Parks that provide for a variety of cultural expressions represent places where residents come together to learn about their own heritage and the heritages of their community.

Preservation of History

California's human history extends back centuries. Parks can preserve the landscapes and artifacts of this lineage. Whether following a guide book on a trail, listening to a docent or ranger explain a feature, or just taking in history by sight, parks play a strong role in preserving a roadmap to the state's communities, economies, and ecology.

Tourism, Jobs and Other Economic Benefits

One cannot travel far in California before seeing a local park, a regional reserve, a national forest or park, or many other types of the state's protected open lands. These lands represent more than just play spaces or scenic wonders — they are strong economic contributors:

- Thousands of people hold jobs in parks and in related programs — rangers, support staff, people who run science programs for kids, wedding planners, and more.

- Thousands of businesses thrive on the support of nearby parks, or recreation generally (sports leagues, hunting, fishing, camping, hiking, etc.) — outfitters, restaurants, hotels, motels, and B&Bs.

- Parks, including state beaches, bring tourists from all over the world — in San Diego, one estimate placed the value of park-related tourism for the county at $40 million, including hotel and food fees, sales taxes, rentals, and other expenditures (see sidebar for statewide analysis).

- Parks increase home values immediately near them by 5–15 percent, according to an estimate by The Trust for Public Land, helping property owners and boosting local property taxes.

- Parks provide "ecosystem services" with large economic benefits — the savings from groundwater capture and cleansing alone are an invaluable but often hidden financial contribution of parks.

- An Outdoor Industry Association report finds that all types of private and public recreation (beyond spending related to public parks) generates $85 billion in consumer spending and 732,100 jobs in California. To learn more go to: https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2017-outdoor-recreation-economy-report/

Economic Value of Public Parks in California

| Park Types (number of) |

Sales* | Jobs** |

|---|---|---|

| City, County and Regional Parks (12,000) | $10 billion | 196,000 |

| State Parks (630, includes all state agencies) | $4.3 billion | 56,000 |

| Federal Parks (500, includes all federal agencies) | $7.1 billion | 61,000 |

| Average Total Per Year | $21.4 billion | 313,000 |

*Sales include travel and related expenditures (lodging, meals,gas) and team and other sports equipment). **Jobs include park personnel and indirect employment from recreation-related expenditures. Park numbers do not include approximately 500 nonprofit and private parks in total CPAD inventory.

Protection of Natural Resources

Another important benefit of parks includes the protection of natural resources needed for all life. Protection roles include:

- Conservation of biodiversity — California is well-renowned for the richness of its plant and animal species, and for their uniqueness. Parks and other protected space are vital to ensure natural balance.

- Green Infrastructure — In metropolitan areas, parks capture rain water and storm flows. These "green solutions" help control sediment, flooding, urban heat island effects and pollution.

- Iconic landscapes — Areas of outstanding beauty are frequently preserved in parks — special view points, coastlines, bays, meadows, valleys, mountain ranges are all vital to California's heritage and well-being, and motivate people to protect and support parks.

The natural resource value of parks becomes more important every year as the press of population growth challenges landscapes and natural systems. This growth is now projected at 20 percent over the next quarter century. (California Department of Finance)

Wetlands...

- Are vital for ecological sustainability, especially migrating birds and many fish species.

- Safeguard water quality, and help with flood water management, shoreline erosion, and groundwater recharge.

- Help manage sea level rise impacts, by softening storm surge and lowering flood heights.

- Provide ecosystem services — economically and socially valuable functions to human society, often worth billions of dollars.

- Offer outstanding recreation — they are magnets for ecotourism, wildlife viewing, fishing, hunting, boating, and paddling.

Wetlands Conservation

The future of wetlands is a critical matter; therefore, each SCORP includes priorities for wetlands.

- Since European settlement, ninety percent of the original inland wetland landscapes of California have been lost. These losses are due to agriculture, urban development, and other human actions.

- Coastal wetland loss is even more severe, with only five percent of original wetlands remaining.

California's Wetland Conservation Policy mandates "no overall net loss and a long-term net gain in the quantity, quality, and permanence of wetland acreage". As such, wetlands are protected by many federal and state laws, regulations and policies to prevent further degradation and destruction.

The California Wetland Monitoring Workgroup includes federal, state and local agencies working to "coordinate monitoring activities, establish priorities, resolve existing inconsistencies, and facilitate communication among agencies and with wetlands conservation stakeholders." This included development of the California Rapid Assessment Method (CRAM) (www.cramwetlands.org) and the California EcoAtlas (www.ecoatlas.org).

Acquisition and wetlands restoration funding needs greatly outweigh resources available — for example, the State Coastal Conservancy estimated the cost for major wetland projects planned and designed in San Francisco Bay and Southern California alone to be at least $2 billion.

III. California Develops New Tools to Assess Park Need

People need the time and financial resources to travel to parks away from their communities. Only the presence of a park within a community can provide immediate daily access for its residents.

How many of the state's 38 million residents have park space in their communities?

This question was central in the development of the Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. The response encompasses two measurements:

-

Which neighborhoods have no park within a half mile?

To determine which residents have parks within walking distance in their neighborhoods, this plan utilizes the standard established in the 1960 California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan that a park should exist within a half mile of neighborhoods, especially to serve "low mobility" residents due to age, income, or physical condition.

-

Which areas fall short of the standard of more than three park acres per 1,000 residents?

Legislation passed in 2008 enacted the Statewide Park Program (Public Resources Code §5642) that defined underserved communities as having a ratio of less than three acres of parkland per 1,000 residents. An area of 50,000 population, for example, would be classified as underserved if it had fewer than 150 acres of parks. This measure is important because it identifies areas where surrounding population density may overwhelm limited park space.

What Californians Say

In surveys by State Parks, 72% of Californians say they walk to parks they most frequently use. This underscores the SCORP focus on the importance of nearby community parks, and is a key factor in how parks can help address health needs.

Results of the SCORP Analysis

This assessment marks the first time statewide comprehensive GIS technology identifies park acreage down to the neighborhood level. No other state has a GIS system of all local, state, and federal parks combined with demographic information that pinpoints parks in communities. This new GIS system helps policy makers, park planners, and the public to assess park space.

The primary findings from this analysis for California indicate:

62% of Californians live in areas with less than 3 acres of parkland per 1,000 residents, a recognized standard for adequate parks

9 million people do not have a park within a half mile of their home

These findings provide a broad overview of the availability of park acreage within residential areas throughout the state, and are not intended to be definite for any particular community's situation. Areas That Are Underserved by Parks

GIS analysis of each census tract in California assessed how many acres of parkland existed per 1,000 residents. Using a standard of 3 park acres per 1,000 residents, tracts were ranked as noted below. This measurement is a starting point for statewide assessment, and should be used as a point of departure for more detailed review in any community.

For this statewide analysis, California State Parks chose census tracts as the area against which to assess the amount of existing parkland in comparison to the 3 acres/1,000 population metric. Census tracts vary in population size, but average approximately 4,000 persons. Note that in some situations, additional parkland may lie at the edge of or very close to of a particular tract, a condition not measured by this analysis.

Mapping Tools for Parks

To obtain detailed information about all communities statewide, park planners and other interested parties can use web mapping tools available through www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP .

- Park Access Tool (PAT)

- Park Acres per 1,000 Residents: shows the ratio of park acreage and income threshold in each census tract.

- Neighborhood Areas with No Parks: identifies neighborhoods that are further than a half mile from any park, includes options to see population density of "no park" areas and income threshold.

- Community FactFinder: analyzes possible new park sites, by creating park and demographic metrics for a half mile area around any site. Also used by OGALS for administering park grants.

- CaliParks.org: a web application that allows anyone to search for any park in California, providing maps, directions and more information about each park.

Illustrations of each of these tools are on the following pages.

"For 40 years my mother, then I, tried to have this lot full of weeds cared for. It was rodent infested and developers dumped here late at night. Everybody is excited waiting for the grand opening. We all fought for this. It brings me a lot of joy seeing the community look out for this park at all times of night while it's being built."

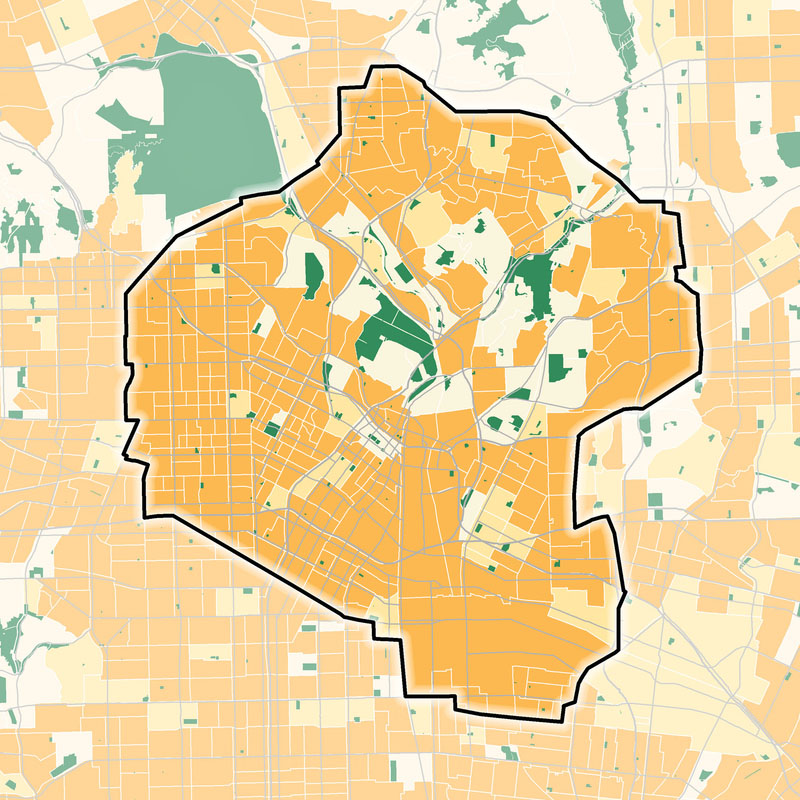

Park Access Tool

Park Acres per 1,000 Residents

Uses: This tool screens for areas that may not meet state recommended standard of 3 park acres per 1,000 residents. Users can evaluate park need areas in every jurisdiction of the state. This web tool provides choices of city, county, legislative districts, etc.

Method: Evaluates census tracts for park acres per 1,000 residents.

Metrics for area of analysis shown:

- Population: 1.1 million

- Park acres: 1,950

- Park acres per 1,000: 1.8

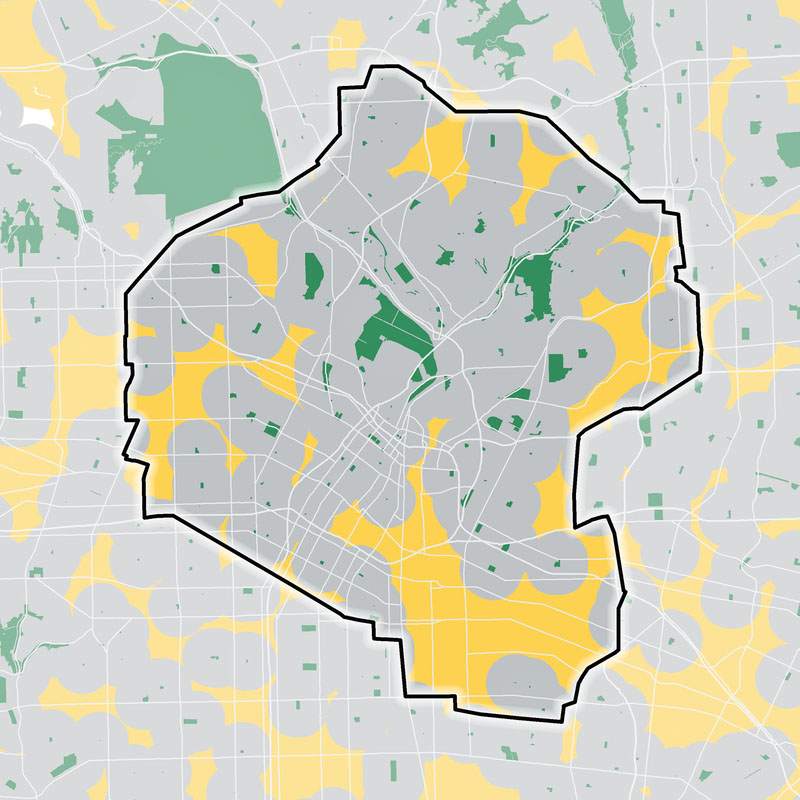

Neighborhood Areas with No Parks

Uses: This tool focuses on areas that lack nearby parks and can be used to guide future park planning.

Method: Defines a half mile radius around all parks in state to determine park area availability.

Metrics for area of analysis shown:

- 16.6% of residents live without any park within .5 miles

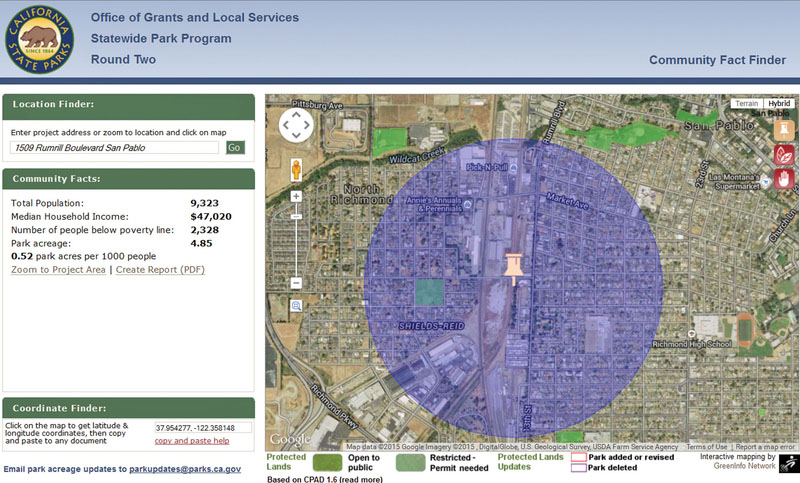

Community FactFinder

Uses: Evaluates the need for parks in immediate areas, based on analysis of a half mile radius to identify a potential project site. FactFinder also supports administration of grant programs.

Methods: Uses CPAD and census data to create analysis of park availability and population profile.

Metrics for area shown:

- Population: 9,323

- Park acres: 4.85

- Park acres per 1,000: .52

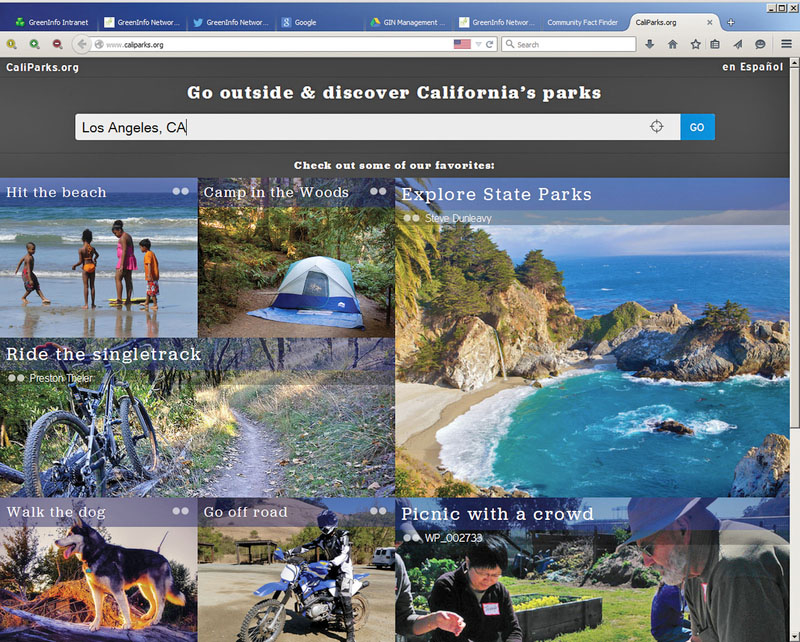

CaliParks.org: Access to Parks

CaliParks.org is a web mapping application that lets anyone find parks in California, and tracks social media posts in parks. It's designed for use on smart phones and to help those who may not yet be fully connected to parks to become more engaged in using them. CaliParks.org is a next-generation parks finder, complementing www.ParkInfo.org which was also used in FindRecreation on the Calif. State Parks web site.

Uses: General public, with a focus on those who are motivated by social media.

Methods: Application developed by Stamen Design, with support from GreenInfo Network and HipCamp, based on CPAD parks data. Funding support from Resources Legacy Fund.

IV. Improving Existing Parks

Even in communities where there is public space devoted to parks and playgrounds, residents are less likely to use parks if they are unsafe, unattractive, poorly designed or maintained.

A recent survey of parks directors across the state showed—by a large margin—an unmet need for maintaining parks due to a deferred maintenance backlog.

Results of the recent State Parks survey of attitudes toward recreation also reflect a desire for safe, well-maintained parks and programs offered in parks.

To improve the use of parks, both facility and program needs must be considered. Addressing these problems requires the active engagement of residents who are in the best position to understand the conditions that lead to the degradation of their parks. Successful collaborations among parks departments, public health and public safety agencies, housing and urban development departments, local nonprofit organizations, and civic-minded businesses and citizens can make the difference in revitalizing parks.

Operating and Maintaining Existing Parks

Although new parks are important, the use and maintenance of existing parks is also critical. As part of the SCORP, OGALS surveyed park agency directors throughout California. A total of 295 directors (approximately 40%) participated in the survey. These directors cited their agency's most important unmet need:

- 55% cited rehabilitation of existing parks to remedy a deferred maintenance backlog

- 19% said a new park in a park deficient area

- 17% said new facilities in existing parks

- 9% said adding or expanding programs such as sports leagues and fitness activities, performing or visual arts, and other recreation and community service programs

"I am really happy this is going up. As a community, we need to think generationally. A whole generation won't have to hear they can't go to a park because it is not accessible, that it will hurt our body. Now we can socialize with kids like us. That is priceless."

What Californians Say About Parks

The department conducted extensive research including its Survey on Public Opinions and Attitudes on Outdoor Recreation in California (SPOA). This survey included online and phone responses from 5,421 adults and 410 young people, ages 12–17. Here's what Californians think about parks (the interactive survey results are at parks.ca.gov/SPOA):

- 63% agree/strongly agree "Open Space is needed where I live" (618 of 978 responses).

- 72% agree/strongly agree recreation programs help reduce crime and delinquency (706 of 979 responses).

- 80% agree/strongly agree recreation programs help improve health (778 of 977 responses).

- 72% agree/strongly agree recreation programs create jobs and help improve the economy (712 of 982 responses).

- 72% walk to get from home to the place they most often visit for recreation (3375 of 4693 responses — phone survey). The remaining 28% drive, bike, or use public transit. This clearly shows local parks matter.

For California youth:

- 88% agree/strongly agree being in the outdoors helps them deal positively with stress.

Youth also identified the need for closer-to-home areas designed for their age, with equipment and programs, as the top solutions to get them to use parks more often.

V. Sharing Success Stories

The ability to respond to the public need for parks will depend, in part, on available financial resources and the ability to effectively share federal, state, and local resources. Although scarce financial resources pose significant challenges, sharing knowledge can benefit everyone.

This SCORP proposes that the network of parks agencies and advocates in California share their greatest achievements and solutions through the establishment of a special clearinghouse. The clearinghouse will foster understanding and the application of successful practices in these key areas:

- Community based planning

- Operations and maintenance

- Water and energy conservation

- Recreational programs

- Other success stories

The following pages illustrate how sharing stories can help agencies find solutions to challenges facing parks in California.

"Children had no place to play. Parents were fined if children played in apartment courtyards, and the school closed the gates after school and on weekends.

We started selling tamales ten years ago to have a park here. The community is very grateful for this park."

Pogo Park — "We drilled capital monies down, into the community, to hire and train local residents to design and build the park themselves. Our motto is to lift up the people at the same time you lift up the place. And it worked. This public project was a magnet that brought out all the goodness and talents of the neighborhood that are so often hidden."

Community Based Planning

Getting meaningful engagement from park users at the start of park planning is a key to community based planning. Residents who live and work in a community understand their park and recreation needs. Projects designed with honest community input yield more successful, practical, safe, popular parks that become a source of community pride. A plan created with residents in the community generates institutional memory, allowing good plans to endure and evolve. OGALS‘ recent Prop. 84 competitive grant program also showed that requiring robust community engagement establishes clear expectations and leads to better projects that are most responsive to community needs.

Operations and Maintenance

Park agencies have used a variety of strategies to supplement limited resources, such as fundraisers, partnerships with sports leagues and non-profit organizations, "adopt-a-park", and weekend clean-up programs. Success stories can include strategies for maximizing existing parks, reusing school facilities, and recruiting volunteers to assist with on-going responsibilities.

The California Parks "Success Stories" Clearinghouse

Success stories are powerful motivators for learning the most effective way to maximize park resources. The California Department of Parks and Recreation is establishing the California Parks "Success Stories" Clearinghouse, and invites all park agencies and organizations to contribute stories. Here's what to do:

- Create a one page description of your success story and a second page of one or more good quality photos, save as one or two PDF documents.

- Email this document to scorp@parks.ca.gov , with "(your agency) Success Story" in the subject line. You can send more than one at a time.

Success stories will be featured at www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP — learn more about submitting success stories on this site.

Success Story: The Art of Community Based Planning

OGALS gained experience through its interactions with local agency grantees from the 2000 and 2002 Bond Act programs. These earlier interactions enabled OGALS to foster new community planning strategies that became integral to the Statewide Park Program.

Community based planning creates an environment for real community input and influence. This strategy to engage residents in the project design process arose from a combination of comments from nine hundred park professionals at twenty focus groups and public hearings conducted by OGALS:

- Meet with Residents Near the Project. Hold park design workshops at convenient locations and times for residents lacking transportation and with various employment and family schedules: Conduct at least five meetings near the project site. This can include "sidewalk" meetings at the project site, presenting at other community meetings, meeting with students during classes, partnering with local organizations, or using volunteers to reduce costs and the need for paid staff. Start with a "clean slate", not a predetermined project design.

- Invite Residents to Provide their Ideas. Outreach to ensure that a diverse group of the community participates in the park design process. Encourage neighborhood youth, seniors, and parents to be a part of the design process so that the needs of different generations are met. Use at least three methods to invite residents and consider language, cultural and physical needs, as well as child care and food.

- During the Meetings: Allow residents to identify their needs and design ideas focusing on key aspects for successful parks:

- Selection of the recreation features and their design.

- Most practical location of the recreation facilities and other features within the park.

- Design ideas for safe public use and park beautification such as landscaping or art additions such as mosaics.

Water and Energy Conservation

Due to the state's current drought, the likely long-term effects of climate change, and increasing costs of water and energy, innovative examples of conservation techniques and sustainable design are sought. These examples can outline how local park agencies educate the public about how sustainable designs can be used in homes, gardens and businesses.

Recreation Programs

Parks can serve as a "one-stop shop" for youth mentoring, parent education, senior wellness, sports and physical training, performing arts, and health and nutrition programs. Some agencies partner or collaborate with other community service providers to provide programs in parks. The Success Stories Clearinghouse will include innovative program examples that have proven to change lives.

Other Success Stories

Additional successes can arise from a variety of practices such as: making parks safer; innovative facilities and technology; community art in parks; partnerships; management practices; creating recreational trails and greenways to provide active transportation corridors from neighborhoods to parks, schools, and workplaces.

El Dorado Park — "El Dorado Park in Fresno is an exciting example of the community collaborating with local organizations and agencies to create and sustain a green space in an impoverished neighborhood with high crime. It took a lot of collaboration and an abundant community attitude to visualize what was possible. With persistence and cooperation from the City's park department, the Boys & Girls Club of Fresno County, a local church, PG&E, two private foundations, and KaBoom! Playground Equipment — the New El Dorado Park and home of a Boys & Girls Club became a reality in 2011."

VI. California's Track Record of Parks Funding

For 150 years, Californians have invested in their parks. Statewide bond acts, annual budgeted expenditures, philanthropic gifts, creative real estate ventures, federal funds, local special taxes and fees — have built 14,000 parks and open space preserves throughout the state. Since 2000, this investment totals over $4 billion — equal to about $100 per resident.

For 150 years, Californians have invested in their parks. Statewide bond acts, annual budgeted expenditures, philanthropic gifts, creative real estate ventures, federal funds, local special taxes and fees — have built 14,000 parks and open space preserves throughout the state. Since 2000, this investment totals over $4 billion — equal to about $100 per resident.

In the last 15 years, California's voters have authorized the following major investments, which have helped address growing needs, illustrated in the chart of bond acts below.

Proposition 12 (2000) provided $780 million for local parks, with other funding for larger parks, forests, open space, water quality and other investments.

Proposition 40 (2002) was similar to Prop. 12, but devoted $946 million for local parks, out of the $2.6 billion authorized by the bond.

Proposition 84 (2006) was strongly aimed at water quality and flood control needs, but provided $457 million for local parks, and other funding for other land conservation.

In addition to these major statewide bond measures, local governments and regional agencies have secured passage of a wide range of special taxes and fees, mostly through ballot measures at the city, county or regional level, raising hundreds of millions for local parks.

The most recent illustration of this investment includes the $368 million Statewide Park Program funded through the Proposition 84 Bond Act of 2006. This program was the largest state grant program in the United States, providing funds for 100 new parks in areas of high need.

OGALS received $2.9 billion in grant requests through 900 applications from Statewide Park Program applicants. All of the $368 million of program funding has now been committed to park projects.

Lessons from Statewide Park Funding in California

While local park taxes, fees and other support has been considerable, two types of statewide funds that aid the nearly 1,000 park-related agencies in California have remained a primary source of new parks: Block Grants (awarded to city/county/districts, usually based on population) and Competitive Grants (awarded by merit for specific categories).

Block Grant Lessons

Strengths: Allocations reach a wide range of jurisdictions — the Per Capita Program (Proposition 40/2002 Bond Act) provided funds to 770 local park agencies. Flexibility of these funds given to local agencies allows high priority maintenance items to be addressed.

Issues: Per capita funds are spread thinly across the state — recent program provided grants averaging $150,000 per project. Non-profit organizations and conservancies were not eligible to apply. Per capita grants do not require applicants to follow statewide SCORP priorities.

Competitive Grant Lessons

Strengths: Grant awards shaped by SCORP priorities or legislative priorities. Average amounts are higher and outcomes likely more substantial (average for the Statewide Park Program was $2.9 million per grant, which led to over 100 new parks).

Issues: Competitive grants cannot fund all applications, as only 10 percent were funded through recent Statewide Park Program — of 900 applications asking for $2.9 billion.

Grants by the Numbers

The Office of Grants and Local Services (OGALS) within the California Department of Parks and Recreation serves local agencies and nonprofit organizations. Since 1964, 20,000 grants administered by OGALS created or improved more than 7,400 parks.

Since 2000, OGALS has:

- Administered 8,400 grants from 34 different grant programs

- Processed 12,800 grant payments totaling $1.8 billion

- Reviewed 5,150 grant applications from 45 competitive grant programs and cycles. Grant applications requested $6.1 billion in funding. Currently OGALS administers 630 park projects totaling $418 million

Major funding sources for OGALS grants have been statewide park, water and natural resources bond measures, when available. Among many other smaller programs, OGALS administers annual Land & Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) funds from the National Park Service, the Habitat Conservation Fund ($2 million/yr.), and the Recreational Trails Program (up to $4 million, depending on Congressional action).

VII | The Action Plan

This SCORP establishes the following actions to address California's park and recreation needs:

Statewide Actions

- Inform decision-makers and communities of the importance of parks.

- Establish educational outreach and partnerships to inform decision-makers at all levels (including foundations, health providers, and other potential funders) about why parks improve the quality of life for communities.

- Improve the use, safety, and condition of existing parks.

- Develop a pilot program through a health and recreation sector partnership designed to improve community wellness. Monitor and report measurable outcomes including a cost-benefit analysis.

- Inform decision-makers and other key opinion leaders about unfunded deferred maintenance needs reported by agency directors.

- Use GIS mapping technology to identify park deficient communities and neighborhoods.

- Inform local agency park planners how to use new GIS tools featured in the 2015 SCORP to scan their jurisdiction for areas that need parks.

- Encourage park agencies to report the creation of new parks or to correct existing CPAD data using a defined reporting procedure.

- Every five years, evaluate progress made towards increasing park access by updating the CPAD data inventory and associated GIS technology tools.

- Increase park access for Californians including residents in underserved communities.

- Encourage park development within a half mile of park deficient neighborhoods to provide easier access.

- Utilize federal grants to create new recreational trails and greenways to provide active transportation corridors from neighborhoods to parks, schools, and workplaces.

- Create and expand programs that transport urban residents to larger regional, State, and Federal parks to experience California's incredible natural and historic legacy.

- Share and distribute success stories to advance park and recreation services.

- Launch an online clearinghouse where California's park and recreation agencies and advocates can share innovative solutions. Success story categories will include community based planning, sustainable park design for water and energy conservation, operation and maintenance, recreation programs, and miscellaneous.

- Provide access to all partner agencies. Encourage agencies to submit descriptions and pictures of success stories to the California Parks Success Stories Clearinghouse established by the Department. (See www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP)

Land and Water Conservation Fund Actions

The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) is a Federal program established in 1964 to provide matching grants for both recreation and natural resource conservation. Section 6(f)(3) of the LWCF Act helps ensure that parkland acquired or developed by the program remains in outdoor recreation use in perpetuity. LWCF also funds the SCORP development. This SCORP's LWCF action plan sets Project Selection Criteria priorities to be detailed in the LWCF Application Guides for local and state agencies (see www.parks.ca.gov/grants_lwcf)

- Give priority to projects that address unmet park and recreation needs, with emphasis on proposals to:

- Create new parks within a half mile of underserved communities;

- Expand existing parks to increase the ratio of park acreage per resident in underserved areas;

- Renovate or create new outdoor facilities within existing parks not currently under 6(f)(3) protection;

- Provide community space for healthy lifestyles, children's play areas, environmental justice, cultural activities, historic preservation;

- Engage community residents during the project concept and design process.

- Increase the inventory of California Wetlands under federal 6(f)(3) protection that also meets public outdoor recreation needs through the efforts of multiple agencies.

- Create new wetlands where they previously existed and have been destroyed.

- Acquire existing but unprotected wetlands to hold in public trust.

- Restore, where needed, the quality of existing wetlands owned by public agencies.

- LWCF grants for wetlands will include public access for recreation and educational opportunities.

- Increase local demand for LWCF grants to utilize federal annual apportionments and Special Reapportionment Account funds in a timely manner.

- Encourage a higher number of project applications.

- Increase the total amount requested per each competitive cycle, enabling California to recommend the most viable projects and to use all LWCF funds available to California.

- Develop tools to enable easy identification of all California LWCF grant projects and their locations.

- Develop a web mapping tool to track and demonstrate the importance of LWCF to California.

Connections

Online access to the SCORP: www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP

This website brings the plan alive by including updates to further expand upon planning efforts. The SCORP is also available through www.parks.ca.gov/SCORP.

General inquiries about the SCORP: scorp@parks.ca.gov

Email success stories to: scorp@parks.ca.gov

Email CPAD parks database updates to: cpad@calands.org

OGALS is a full-service organization dedicated to developing grant programs, administering funds, providing technical assistance, and building partnerships.

2015 SCORP Development Team

- Sedrick Mitchell, Deputy Director, External Affairs

- Jean Lacher, Chief, Office of Grants and Local Services

- Viktor Patino, Manager

- Jana Clarke, Supervisor

- Lowell Landowski, Analyst

This report was written and designed by OGALS in collaboration with GreenInfo Network (www.greeninfo.org), a nonprofit that supports other public groups and agencies with geospatial technology, and Ison Design.

Photography by Brian Baer, Senior Photographer, California State Parks

Focus Group Participants

OGALS wishes to thank the following representatives for their participation to develop this 2015 SCORP:

- Bike SD — Samatha Ollinger

- Boys and Girls Clubs of Fresno — Diane Carbray

- Cal South Soccer Foundation — Shirley Ramirez

- California State University, Fresno — Jenna Chilingerian

- California Center for Public Health Advocacy — Kanat Tibet

- California Police Activities League — Gregg Wilson

- California Dept. of Health NEOPB — Leslie Kaye

- California Project Lean — Katherine Hawksworth

- California State Parks — Brian Ketterer

- CANFIT — Arnell Hinkle

- Central California Obesity Prevention Program — Genoveva Islas

- Central California Obesity Prevention Program — Jesse Tedrick

- ChangeLab Solutions — Ian McLaughlin

- City of Anaheim — Terry Lowe

- City of Avenal — Steven Sopp

- City of Chula Vista — Kristi McClure

- City of Coachella — Jacob Alvarez

- City of El Centro — Stacy Cox

- City of El Centro — Marcela Piedra

- City of Fresno — Irma Yepez-Perez

- City of Fresno — Manuel Mollinedo

- City of Long Beach — George Chapjian

- City of Los Angeles — Mike Shull

- City of Oakland — Lilly Soo Hoo

- City of Parlier — Israel Lara

- City of Parlier — Juan Montano

- City of Paramount — Steven Coumparoules

- City of Perris — Sabrina Chavez

- City of Perris — Cynthia Quintero

- City of Perris — Josh Estrada

- City of San Diego — Herman Parker

- City of San Francisco — Toni Moran

- City of San Jose — Yves Zsutty

- City of San Jose — Julie Edmonds-Mares

- City of San Pablo — Mike Heller

- City of Santa Ana — Ron Ono

- City of Selma — Mikal Kirchner

- City of Stanton — Julie Roman

- City of Vista — Donna Meester

- City Slicker Farms — Ariel Dekovic

- Community Action Partnership of Orange Co. — Belinda Ong

- Community Action Partnership of Orange Co. — Ann Mino

- Community Health Councils — Heather Davis

- Contra Costa County — Coire Reilly

- County of Fresno — David Chavez

- County of Fresno — Amalia Madrigal

- County of Los Angeles — Norma Garcia

- County of Sacramento — Jeff Leatherman

- County of San Diego — Brian Albright

- County of Riverside — Gayle Hoxter

- County of Sonoma — Elizabeth Tyree

- County of Stanislaus — Merry Mayhew

- East Bay Regional Park District — Jeff Rasmussen

- Healthy and Active Before 5 — Tonya Love

- Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust — Alina Bokde

- Latino Health Access — Nancy Mejia

- Little Tokyo Services District — Scott Ito

- Lao Family Community Development — Chaosarn Chao

- Lao Family Community Development — Kathy Chao Rothberg

- Local Government Commission — Kate Meis

- Los Angeles Conservation Corps — Bruce Saito

- Marin City — Johnathan Logan

- Monument Impact — Ana Villalobos

- Ocean Discovery Institute — Carla Pisbe

- Pogo Park, Richmond — Ed Miller

- Pogo Park, Richmond — Toody Maher

- Richmond Community Foundation — Erwin Reeves

- SAY San Diego — Karen Lenyoun

- SAY San Diego — Beatrice Lomer

- SAY San Diego — Ashlee Bradshaw

- SAY San Diego — Mary Baum

- San Diego River Park Foundation — Rob Hutsel

- SE Fresno Community Economic Development Association — Jose Leon Barraza

- Sunrise Recreation and Parks — Dave Mitchell

- The City Project — Robert Garcia

- Tony Hawk Foundation — Peter Whitley

- Trust for Public Land — Tori Kjer

- Trust for Public Land — Mary Creasman

- Westside Youth, Incorporated — Dino Perez

- Westside Youth, Incorporated — Augie Perez

All photos by Brian Baer, Senior Photographer, California State Parks, with additional photos from:

- Front page: far left image: Ropes Challenge Course, Courtesy of Office of Community Involvement; far right image: Anaheim Cove Trail, Courtesy of City of Anaheim

- Executive Summary: Stock image

- Chapter 1, Golden Gate Park: Wikipedia, author "WolfmanSF"

- Park Partners Responding to Park Needs: top right image: Courtesy of Office of Community Involvement; third image from top: adaptive water ski, Courtesy of U.S. Adaptive Recreation Center; bottom image: Courtesy of Hesperia Recreation and Park District

- Physical, Mental and Social Health: top image: Courtesy of City of Paramount

- Tourism, Jobs and Other Economic Benefits: Stock image

- Water and Energy Conservation: Courtesy of Santee Lakes Recreation Preserve

- Recreation Programs: top image: Courtesy of Office of Community Involvement

- Other Success Stories: Courtesy of Boys and Girls Clubs of Fresno County

This State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan is dedicated to the people of California and the agencies and organizations that manage our incredible system of parks and open space preserves.